Post Written by Lawrence Tabak, DDS, Ph.D.

As many as 2.5 million Americans live with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, or ME/CFS. It is a serious disease that often develops after infection, leaving people critically ill for decades with pain, cognitive impairment, severe fatigue, and other debilitating symptoms.

ME/CFS can have many causes, so it doesn’t affect everyone the same way. This makes researching this disease particularly difficult.But the NIH is currently supporting ME/CFS Specialized Research Center It is hoped that increased collaboration among scientists will unravel biological complexities and provide answers for ME/CFS patients and their families.

So we’re excited to share some progress on this front from our two NIH-funded ME/CFS Collaborative Research Centers. The findings were published in his two papers in the latest issue of the journal. Cell hosts and microorganismsadds further evidence linking ME/CFS to a unique disruption of the trillions of microorganisms that naturally live in our digestive tracts, called the gut microbiome [1,2].

At the moment, the evidence establishes an association rather than a direct cause-and-effect relationship, meaning further research is needed to pinpoint this clue. However, this is a solid clue and suggests that imbalances in specific bacterial species living in the gut may be used as measurable biomarkers to aid in accurate and timely diagnosis of ME/CFS. There is. It also represents a potential therapeutic target to explore.

The first paper was led by Julia Orr and colleagues at the Jackson Laboratory in Farmington, Connecticut, and the second paper was led by Brent L. Williams and colleagues at Columbia University in New York. . Although the cause of ME/CFS remains unknown, the research team recognized that the disease involves many underlying factors, including changes in the metabolic, immune, and nervous systems.

Previous studies have also pointed to the role of the gut microbiome in ME/CFS, but these studies have been limited in scale and ability to reveal precise microbial differences. Given the close relationship between the microbiome and the immune system, the teams behind these new studies will look deeper into the microbiome of more people, with and without ME/CFS. We have started.

At the Jackson Laboratory, Oh, Derya Unutmaz and colleagues collaborated with other ME/CFS experts to study microbiome abnormalities during different stages of ME/CFS. They analyzed clinical data (medical history) and fecal and blood samples (biological history) of 149 ME/CFS patients, including 74 diagnosed within the past four years and another 75 diagnosed more than 10 years ago. ) were compared. . Additionally, 79 people were recruited as health volunteers.

Their detailed microbial analysis showed that the shorter-term ME/CFS group had less microbial diversity in their gut than the other two groups. This suggests that during the early stages of the disease, the previously stable gut microbiome becomes disrupted, or imbalanced. Interestingly, people who had been diagnosed with ME/CFS for a long time apparently re-established a stable gut microbiota comparable to healthy volunteers.

Oh’s team also examined detailed clinical and lifestyle data from participants. We found that by combining this information with genetic and metabolic data, ME/CFS can be accurately classified and differentiated from healthy controls. Through this classification approach, we found that long-term ME/CFS patients have a more balanced microbiome but exhibit more severe clinical symptoms and progressive metabolic abnormalities compared to the other two groups. I discovered that there is.

In the second study, Williams, W. Ian Lipkin of Columbia University, and their colleagues conducted a geographically diverse study of 106 ME/CFS patients and another 91 healthy volunteers. They also analyzed the genetic composition of gut bacteria in fecal samples taken from different groups. Their extensive genomic analysis revealed important differences in microbiome diversity, abundance, metabolism, and interactions between different key species of gut bacteria.

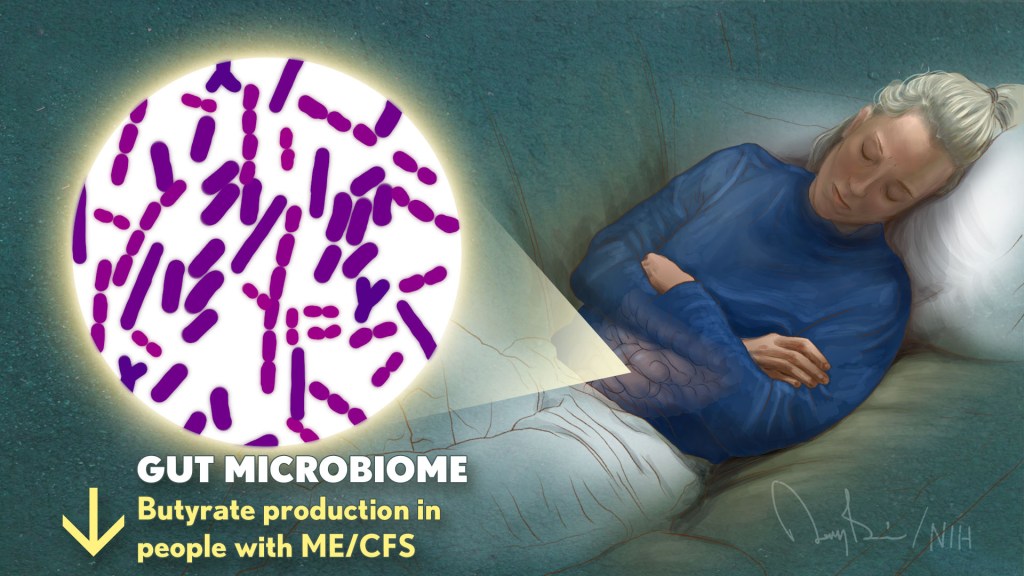

Of particular note, Williams’ team found that ME/CFS patients had abnormally low levels of several bacterial species, including: Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (F. Prausnitzi) and eubacteria rectum. Both bacteria ferment indigestible fiber in the digestive tract to produce a nutrient called butyrate. Interestingly, Oh’s team also uncovered changes in several butyrate-producing microbial species, including: F. Prausnitzi.

Further detailed analysis in Williams’ lab confirmed that the observed reduction in these bacteria was associated with decreased butyrate production in ME/CFS patients. This is of particular interest because butyrate serves as the main energy source for the cells lining the intestine. Butyrate provides up to 70% of the energy needed by these cells while supporting intestinal immunity.

Butyrate and other metabolites found in the blood are important in regulating immune, metabolic, and endocrine functions throughout the body. It also contains the amino acid tryptophan. The Oh team also found that gut bacteria associated with tryptophan breakdown were reduced in all ME/CFS participants.

Although there were fewer butyrate-producing bacteria, other microorganisms associated with autoimmune diseases and inflammatory bowel disease increased.Williams’ group also has a large amount of F. Prausnitzi were inversely associated with fatigue severity in ME/CFS, further suggesting a possible link between these gut bacterial changes and disease symptoms.

It is exciting to see this more collaborative approach to ME/CFS research begin to open up the biological complexity of this disease. More data and new clues will emerge in the coming months and years. We sincerely hope that they bring us closer to our ultimate goal: to help millions of ME/CFS patients recover from this terrible disease and get their lives back.

I also want to mention that the NIH will be hosting a research conference on ME/CFS later this year on December 12-13. The conference will be held in person at the NIH in Bethesda, Maryland, as well as virtually. We will also highlight recent research advances in this field. NIH will post information about this meeting in the coming months.surely Please check againif you want to join.

References:

[1] Multi-omics of host-microbiome interactions in short- and long-term myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)). Xiong et al. Cell host microorganism. 2023 2 8;31(2):273-287.e5.

[2] Lack of butyrate production capacity in the gut microbiome is associated with impaired bacterial networks and fatigue symptoms in ME/CFS. Guo et al. Cell host microorganism. 2023 February 8;31(2):288-304.e8.

Link:

About ME/CFS (NIH (National Institutes of Health)

ME/CFS resources (NIH (National Institutes of Health)

Trans-NIH Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Working Group (ME/CSFnet.org)

Advances in ME/CFS research (NIH (National Institutes of Health)

brent williams (Columbia University, New York)

Julia Oh (Jackson Laboratory, Farmington, CT)

video: Perspectives on ME/CFS featuring Julia Oh (Vimeo)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. National Institute on Drug Abuse. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. National Center for the Promotion of Translational Science.National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of General Medical Sciences