written by Sharon Reynolds

Many people receive chemotherapy directly after surgery for colorectal cancer that has started to spread beyond the initial site. The idea behind this postoperative, or adjuvant, treatment is to reduce the chance that the cancer will come back elsewhere in the body, thus allowing more people to be cured of cancer.

But there is still no way to predict who really needs this additional treatment and who can safely skip it and avoid the associated side effects.

Results of a new study suggest there may be a promising way to identify those who need postoperative chemotherapy and those who do not.

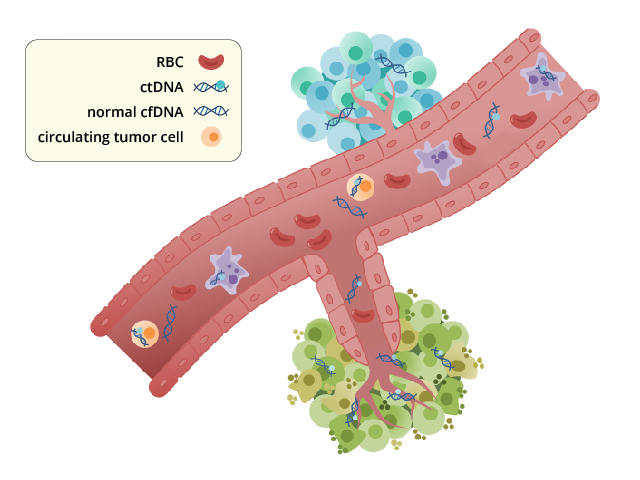

The study found that the presence of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), or fragments of genetic material leaked from tumors into the bloodstream, Predict which patients will benefit from the chemotherapy they receive. In other words, among ctDNA-positive patients, those who received chemotherapy lived longer without cancer recurrence (recurrence) than those who did not receive chemotherapy.

And, importantly, those with a negative ctDNA test likely did not need chemotherapy immediately after surgery. In other words, there was no evidence that chemotherapy helped people live longer without recurrence.

The results of the study, called BESPOKE CRC, were sponsored by Natera, Inc., which manufactures the ctDNA test used, and were presented on January 20 at the ASCO Gastrointestinal Cancer Symposium. Results from another study using the same test, presented at a symposium by a Japanese research team. ctDNA testing showed similar features. Colorectal cancer.

The ctDNA measurements obtained in this study were obtained with a test called a liquid biopsy and were not initially used to select treatments for individual patients. However, the results of the liquid biopsy were provided to participants and their care teams to see if the results changed previously determined treatment plans, said Weil, one of the study’s principal investigators. Pashtun Murtaza Kashi, M.D., M.A., of Cornell Medicine, explained.

However, the results obtained in the BESPOKE and Japanese studies demonstrate that ongoing clinical trials testing ctDNA-based decisions about whether to use adjuvant chemotherapy are safe and very reasonable to conduct. It’s strong enough to guarantee that there is, he said.

“We believe that about 60% of people [with this type of colorectal cancer] It is curable with surgery,” said Carmen Allegra, M.D., special consultant for gastrointestinal cancer treatment in NCI’s Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnostics. He was not involved in this study. “And we don’t want to expose these patients to chemotherapy and its side effects unless necessary.”

But ctDNA could also help identify people who would benefit from more aggressive treatment after surgery or who might want to participate in clinical trials for experimental treatments, Dr. Kasi said. .

Two ctDNA tests are already commercially available and used in some clinics to monitor colorectal cancer recurrence. “The problem is we still don’t really understand how to use it,” Dr. Allegra says.

Currently, if a patient has a positive ctDNA test but imaging tests show no signs of cancer recurrence, it is uncertain whether additional treatment will be started immediately, he explained.

He added that the ongoing trials are expected to provide the guidance needed to understand how to best utilize ctDNA test results to guide patient care.

Track hidden cancer cell signatures

The idea of liquid biopsies to measure ctDNA is not new. The technology is being widely tested to monitor cancer patients and potentially detect some cancers early, before symptoms develop.

In terms of guiding treatment, there are two potential uses for such technology: prognostic and predictive testing. Prognostic tests can measure how likely the cancer is to come back after treatment. Predictive tests can help people learn whether a particular treatment is effective against a person’s cancer.

Together, these two types of information could be used to better tailor treatment for colorectal cancer. Although researchers had hoped that ctDNA testing would play these roles, open questions remained about its actual prognostic and predictive ability.

In early 2020, researchers led by Dr. Kasi enrolled approximately 1,800 people in the study. BESPOKE CRC Research. Results from the initial 623 participants were presented at his ASCO Symposium in 2024.

All BESPOKE participants had stage II or stage III colorectal cancer. Cancer at these stages spreads in or through the wall of the colon or rectum and sometimes to nearby lymph nodes, but it does not spread to distant parts of the body.

This study was not a clinical trial in which participants were randomly assigned to different groups. All participants underwent surgery and, if determined by their care team, chemotherapy.

In addition to standard monitoring for cancer recurrence, which includes imaging and blood tests for a protein called CEA, study participants underwent ctDNA testing every month after surgery, every three months for the next year, and then for the duration of the study. I had a ctDNA test every 6 months. Until the cancer came back.

Clear differences in benefit with chemotherapy

Of the 623 study participants, 381 received chemotherapy starting about three months after surgery based on how abnormal the cancer cells removed during surgery looked under the microscope and other risk factors. It started.

Of the participants who received chemotherapy, 85 had at least one positive ctDNA test. The other 296 patients who received chemotherapy had negative ctDNA tests.

For people with positive ctDNA tests, chemotherapy had clear benefits. The median time these patients lived without their disease returning (a measurement called disease-free survival) was nearly 18 months, compared to patients with positive ctDNA tests who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy. The survival period was approximately 7 months.

However, for those with negative ctDNA tests, chemotherapy did not make much of a difference. More than 90% of people without measurable ctDNA survived for a median of more than 2 years without disease recurrence, regardless of whether they received chemotherapy after surgery.

Of the more than 500 participants who initially tested negative for ctDNA, 14 ultimately received positive test results. These patients were more likely to have their disease return than those whose tests remained negative. However, by 15 months after surgery, the likelihood of a patient going from her ctDNA negative to ctDNA positive decreased sharply.

Of the 101 patients whose cancer eventually returned to other organs during follow-up, 40 had so-called rare metastatic disease. This is where the patient has only a few, usually small, metastases. A significant number of these tumors were first detected by ctDNA testing during the study, Dr. Kasi explained.

He continued that for some people with oligometastatic disease, treatments such as surgery and radiation to the metastatic sites remain options. “And we know this from experience. [such treatment] Helps improve survival rate. So ctDNA [testing] It may help increase the number of people who benefit from such an approach. ”

Can ctDNA testing guide treatment from the beginning?

Studies are currently underway to test whether ctDNA measurements can be used to guide colorectal cancer treatment from the outset.

In one of these studies of early-stage colon cancer patients, conducted at the NCI-funded National Clinical Trials Network, patients with positive ctDNA tests after surgery received a standard chemotherapy regimen. or randomly assigned to receive chemotherapy. A more intensive regimen than usual. “Because the cancer in these people is much more likely to come back,” Dr. Allegra explained.

In contrast, trial participants with a negative ctDNA test will be randomly assigned to receive only surveillance after surgery or standard chemotherapy. Results from that part of the study are expected to provide a clearer picture of who can safely skip adjuvant chemotherapy, Dr. Allegra added.

BESPOKE’s results provide assurance that such tests are safe, Dr. Kasi explained.

“When this study was designed several years ago, even considering the use of ctDNA to guide adjuvant chemotherapy…was fraught with many polarizing opinions. These results… “We are ready for ongoing clinical trials,” he said.

For now, BESPOKE researchers will continue to follow participants to see if their doctors used information from the ctDNA tests to change treatment strategies in real time, and whether that affected their risk of cancer recurrence. I’m planning to check it out.

emphasizes the need for better treatment

Dr. Allegra said the one elephant in the room is that about a quarter of patients with stage II or III colorectal cancer will not be cured with adjuvant chemotherapy. For someone who has received all the standard treatments and still has her ctDNA in their blood, “What do you do for that patient?” he asked.

Clinical trials are currently investigating ways to improve outcomes in this scenario, including using different chemotherapy drugs, administering second-line chemotherapy earlier, and testing immunotherapy for tumors with specific genetic characteristics. Dr. Allegra explained that they are considering the following.

But BESPOKE’s findings from patient-reported results show that even if a ctDNA test result is bad news, people want to know what’s going on inside their bodies as soon as possible. Dr. Kasi said that suggests that And he added that he wants to make common decisions about future care.

“This test [provides] powerful insight about [whether] think about [the] The next treatment and clinical trial options are available much sooner,” Dr. Kasi said. “It’s also going up. [recurrent] Cancer is detected 6 to 9 months before it is detected on a scan. “This is an essential tool in our toolbox and I think it will continue to be here,” he said.

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.