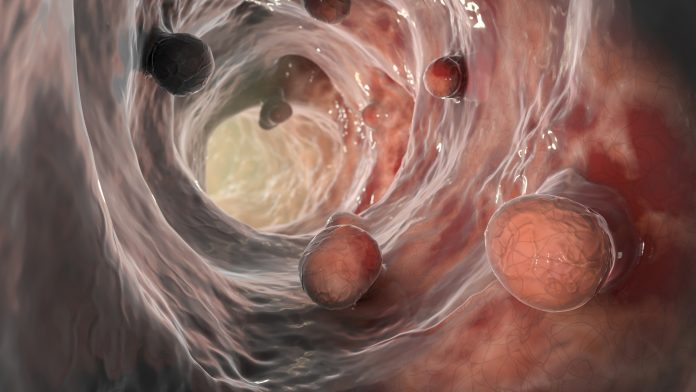

Previous studies have shown a link between high blood cholesterol levels and various cancers, including colorectal cancer. However, it is not clear whether lowering cholesterol can prevent colorectal cancer. Now, Weill Cornell Medicine researchers have shown that hard-to-detect colorectal precancerous lesions known as serrated polyps exist in mice, and that the aggressive tumors that develop from them are stimulated by increased production of cholesterol. I have found that it is highly dependent on Their findings point to the possibility of using cholesterol-lowering drugs to prevent or treat such tumors.

The survey results are nature communications In an article titled “Enhanced SREBP2-driven cholesterol biosynthesis due to PKCλ/ι deficiency in intestinal epithelial cells promotes aggressive serrated tumor formation”

“The metabolic and signaling pathways that control the development and progression of aggressive mesenchymal colorectal cancer (CRC) through the serrated pathway are poorly understood,” the researchers wrote. “Although relatively well-characterized BRAF-mutated cancers, their poor response to current targeted therapies, difficulty in pretumor detection, and difficulty in endoscopic resection make identifying their metabolic requirements a priority. Here we show that phosphorylation of SCAP by an atypical PKC (aPKC), PKCλ/ι, promotes its degradation and inhibits the processing and activation of SREBP2, a master regulator of cholesterol biosynthesis. Prove it.”

The researchers analyzed mice that developed serrated polyps and tumors and detailed the cascade of molecular events in these tissues that lead to increased cholesterol production.

“Serrated-type polyps and tumors are not currently treated differently than other colorectal tumors, but as our study shows, they have unique metabolic vulnerabilities that can be targeted. ” said study co-author Jorge Moscato, Ph.D., Homer T. He is the Hurst III Professor of Oncology in Pathology, Associate Professor of Cellular and Cancer Pathobiology in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, and Weil He is a member of the Sandra & Edward He Meyer Cancer Center at Cornell Medical College.

The other co-senior author is Dr. Maria Diaz-Meco, the Homer T. Hearst III Professor of Pathological Oncology and a member of the Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine. The study’s lead author is Dr. Yu Muta, a postdoctoral fellow in the Moscat/Diaz-Meco lab.

“Clinical trials of statins to prevent colorectal cancer have yielded conflicting results,” Diaz-Meco said. “Our findings suggest that targeting cholesterol may have a preventive but selective effect only on this serrated type of polyp or tumor.”

Tumors that develop into serrated polyps account for approximately 15% to 30% of colorectal cancers and are particularly invasive and contain many “metaplastic” cells that are resistant to treatment.

Several years ago, the Moscat/Diaz-Meco team linked serrated polyps and tumors to low levels of two enzymes known as aPKC. They showed that mice engineered to lack these aPKC enzymes in their intestinal lining reliably form serrated polyps and subsequently aggressive tumors.

In this study, the scientists found that cholesterol synthesis was significantly upregulated in the serrated tumors and even in the intestinal tissue of these mice, suggesting that cholesterol may be an early driver of tumor development. are doing.

Researchers have shown how the absence of the aPKC enzyme, particularly in metaplastic tumor cells, triggers the activation of a transcription factor called SREBP2 that switches on cholesterol production.

This result indicates that targeting cholesterol may be an effective strategy for the treatment and prevention of serrated colorectal tumors. The Moscato Institute and the Diaz-Meco Institute now hope to launch an early clinical trial of a cholesterol-lowering intervention in patients who have had serrated colorectal polyps removed.

“Right now, if these polyps are caught early during a colonoscopy, they can be removed and patients can only hope that they don’t come back,” Moscato said. “In the future, we hope to develop more aggressive ways to prevent this highly aggressive cancer before it progresses completely and becomes difficult to treat.”

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!